Dhansing and Pankali

because you care

Dhansing’s Story

Dhansing is one of the young blind men I have helped in Nepal. His name does not mean “dancing,” but to me he will always be a dancer. He’s from a very remote area in the west, one of the least developed regions on earth.

I first met him in the predawn at Deepnath’s house. He wore a light jacket that was not thick enough to ward off the chill. There was nothing attractive about him. His clothes were threadbare and faded. He could barely afford soap, much less deodorant. When I met him, I shook his hand and laid my left hand on his shoulder to let him know exactly where I was standing. His hand was cool, his grip tentative, and his shoulder thin.

I greeted him in English and he laughed, unaccustomed to my foreign speech. He tilted his head in the peculiar way that blind people do, looking at me from that space between his ear and his eye. His sunglasses, askew and greasy, reflected the dim glow of a cooking fire that burned just inside the home. The teapot boiled over, and he knew it before any of us. He said something in Nepali, and someone scrambled inside to lift the hissing kettle from the fire.

We had breakfast together—sweet water-buffalo-milk tea, hot barley naan with ghee, boiled potatoes. I asked him to tell us how he lost his sight.

When he was an infant, he had an infection in both eyes. There was no medical care in his valley. His parents took him to a village shaman who treated him by pouring hot oil mixed with herbs into his eyes. He lost his sight. As he told his story, one of the young Nepali men with us grew angry and said, “You should tell us who that man is. He must still be alive. He needs to be held accountable for what he did to you.”

Dhansing leaned toward the young man who had spoken, found his arm and rested his hand there, and said quietly, “I’ve let it go.”

It was stunning, and I fought back tears for quite a long time. This young blind man had accepted his past and truly forgiven his enemies. He had no bitterness. His life was beautiful.

Later that day we walked to the hostel where he lived with about thirty other blind children. The walk was not that long, maybe thirty minutes, but I fretted the whole way. Dhansing walked ahead of us, led by his friend Datta, who is what we would call legally blind. Datta has cataracts and can only see through a tiny window on the edge of his right eye. He peers at the world through that little portal, reading messages on his mobile phone from an inch away, scanning his path in quick, birdlike glances, greeting folk with a sideways gaze. I don’t know how much he can see, but it can’t be much. He stumbles often.

Dhansing held Datta’s arm just above the elbow and walked a little behind and to the left. They led us along a single-track path that wound along the edge of a steep slope. We weren’t in big mountains, but the drop-off to the left was at least a five-hundred-foot fall. The two blind men stumbled often, sometimes precariously near the edge of the trail. I followed closely behind, reaching for them every time they faltered. There were six of us traveling together, and the Nepalis ignored the stumbling blind men. After a while I realized Datta and Dhansing knew what they were doing, and I relaxed.

From behind the blind men, I began to appreciate their gait. They danced together over that rock-strewn path, sliding their feet along to sense the stones and guiding one another with subtle finger movements and shifts in their positions. They didn’t cling to one another or grasp for support, and what at first appeared to be a halting manner was not that at all. They danced along that precarious path, their choreography as skillful as any I have seen on stage.

We provided for Dhansing for more than six years. He finished his education, found a job teaching in a Nepali government school, rented a little village house, and married one of the girls in our blind children’s home. He was twenty-one and she was nineteen when they married.

In a few months, they were pregnant. On November 5, 2013, Dhansing’s wife, Pankali, gave birth to a beautiful six-pound, six-ounce little girl. I was anxious to see the child, hoping that her sight was all right. The baby was gorgeous. She had clear skin and bright eyes, and gazed with alert and normal vision. They asked me to name the baby, and with the help of my Nepali friends, I named her Rosanie—“guiding light.”

It’s difficult to describe how moving that experience was for me. I thought of how that beautiful, sighted little girl, even as a toddler, would lead her mother and father through life. I thought of her playing tricks on her mom, hiding as quiet as a mouse in the corner and moving things in the room. And I thought of that bittersweet day when Dhansing and Pankali would give their pair of eyes to a man who would take Rosanie as his wife, a sacrifice of love as in “The Gift of the Magi.”

I have received far more from Dhansing than I have given him. I have learned the beauty of letting go. To me, his name is Dancing.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

People often feel sorry for me. I don’t feel sorry for myself, but I have to admit that sometimes I use my handicap to my advantage. Datta and I once decided to travel to Nepalgunj to visit the church there. We had heard about it from Deepnath, but we wanted to see it for ourselves. At that time the road was very bad, and some sections were not yet built. It was at least a five-day journey for a sighted person. For us it would take even longer. And besides, we didn’t have enough money for the bus fare from the market below Manma to Nepalgunj.

We walked to Jumla town, which took us a full day. Nepal was in a contested national election, and the United Nations had posted international monitors in the rural areas to make sure the Maoists did not intimidate voters. We heard that UN helicopters were making supply runs from the Jumla airport to Nepalgunj.

The helicopter was not there when we reached Jumla, so we sat at the airport and waited two days. We had only a little money, but some people there gave us some chapattis and some tea and a few eggs. On the third day, I heard the helicopter coming up the valley. It made deep thumping sounds, like the sound of a festival drum. I heard it for about five minutes before it reached us. When it landed, a strong wind hit us and blew my scarf away. The thumping stopped, and a high whining sound slowly dropped in pitch until all was quiet.

I heard the pilot tell the workers to unload the supplies as quickly as they could. The afternoon winds were picking up, and he wanted to return before the wind was too strong. He walked past us, and I knew he was going out of the security fence, probably to get tea. Datta and I waited until the men had unloaded the helicopter. When they passed us, it sounded like they were pushing a large wheeled cart. We waited a few more minutes, and I said to Datta, “Let’s get on the helicopter.”

We walked over to the machine and felt our way along its side. It was huge, much larger than I thought it would be. There was a big opening in the side, and we climbed in. We could not find any seats, so we sat on the floor in the back.

When the pilot returned, he said, “Hey! You guys get out of there!”

“We need to go to Nepalgunj,” I said.

“Well, you can’t go on this flight. This is an official UN helicopter. It’s only for humanitarian work.”

“We are blind,” I said. “That is humanitarian work. And we need to go to Nepalgunj.”

We argued with him for a few minutes, but he could see that we weren’t going to leave the helicopter. Finally, he laughed and said, “Hold on tight. This will be a bumpy ride!”

I have never in my life heard such a roar, and when we lifted off, I felt strange, as if I were swinging in all directions at once. I got sick and threw up on the floor. Datta got sick too, but in about an hour, we were in Nepalgunj. The pilot said we shouldn’t worry about the mess we made.

We have a very difficult life up in the mountains. I always felt that I was a burden to my family. I am strong, and even as a child, I did many things to help. I can cook and thresh rice and chop wood for the fire, but I cannot do much work in the field or find firewood or build a house. I’ve always been a burden to them. My family heard there was a blind hostel in our area where I could receive an education, and they took me there. We walked to the hostel in one day, but it was a very long day.

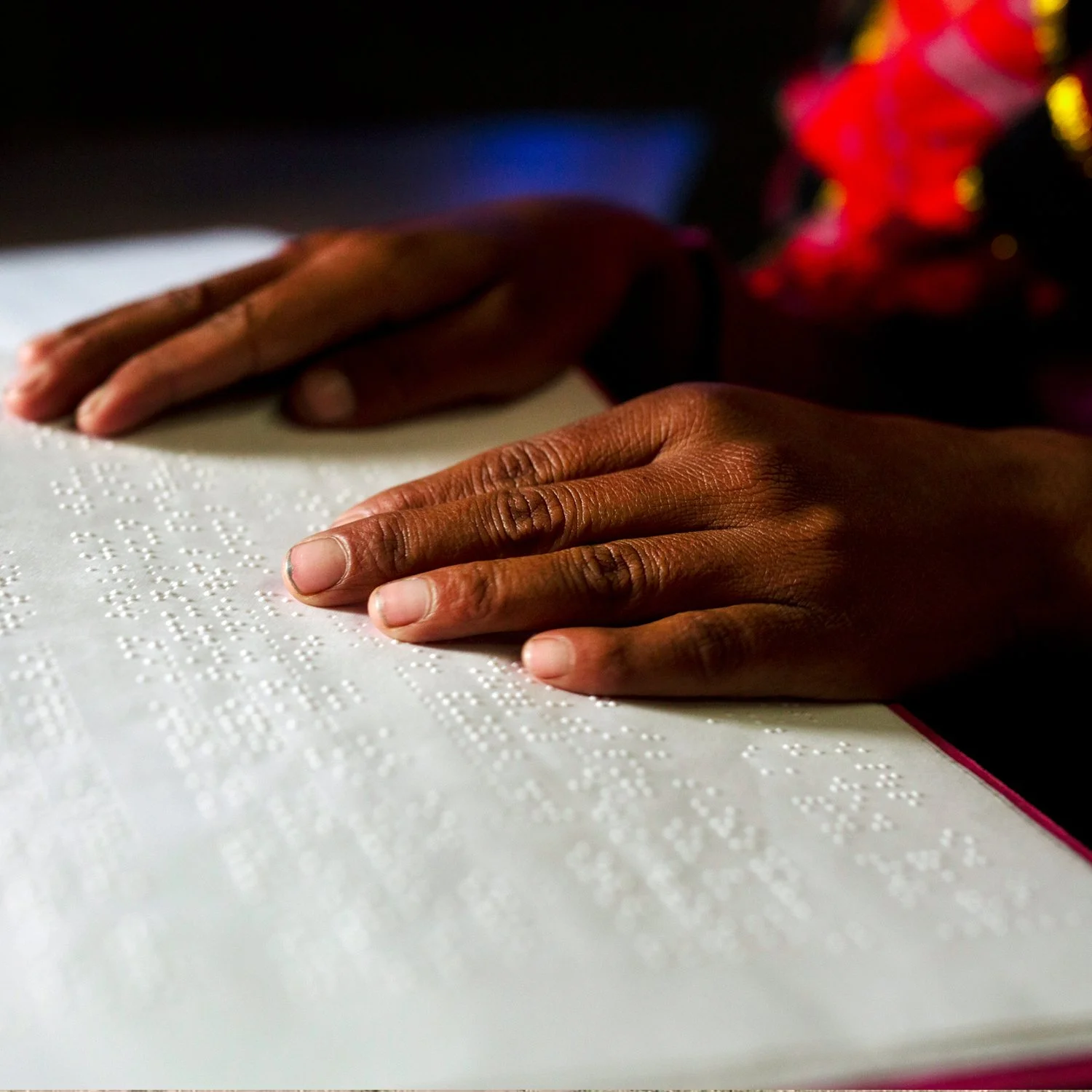

Foreigners from Europe supported the school, but they had never visited. The conditions were very bad. The stone house was broken, some of the walls with cracks large enough to put your hand through. It was very cold in winter, and we slept on mats on a dirt floor, huddled together to stay warm. There was not much food, and I was sick often. But they had Braille books and a teacher who taught us to read. I didn’t care about my suffering. I was hungrier to learn than I was to eat.

I had been in the school for about five years when a foreigner came to visit us. He was an American, and everyone called him Pastor Rick. Not long after his visit, the Europeans who were helping the school stopped sending money. We all hoped that the American would help us.

We ran out of food, and about half of the children went home. I stayed and was about to give up hope when we received word that the church in Nepalgunj would help us. They sent us food, warm clothes, blankets, and even shoes.

Pastor Rick promised to build us a new home. I did not expect it to happen. I thought that by the time the house was completed, I would be finished with my schooling, but within two years, it was done.

It was a wonderful place, clean and large. It had indoor toilets and showers and running water, and after a year we had electricity. There was even a wood stove in the big room that we used in the winter to keep warm. I had never lived in such a nice place. People tell us it is the best building in our valley. A team of Tharu and Nepali men came from the Nepalgunj church to build it. They were very good workers.

Pastor Rick had asked us how we wanted the house built, and we all said we wanted cement floors and smooth walls. We told him we love smooth surfaces, as it makes it much easier for us to keep everything clean. He built it just like we asked.

I loved one of the girls in the school, but no one knew. Her name was Pankali. I knew she was beautiful because I overheard a woman in the village say, “Such a pretty girl. It’s a shame she is blind.”

I didn’t care if she was pretty. I loved her because she was intelligent, and I loved her voice. She did not sing like some of the other blind girls. Her voice was low, like a whisper, and not suited for song. But she spoke gracefully, and she laughed often. We were about the same age.

We sat alone one day warming ourselves in the morning sun. We had been talking, mostly about our studies, and I asked her if I could touch her. It was a very inappropriate thing to ask, and my heart was pounding so heavily that I could hardly hear her whispered answer. “I don’t mind,” she said.

I gently grazed the side of her face with my fingers. I could scarcely control my trembling. She was smooth, like the soft cool of the inner lining of a down-filled jacket. I thought to touch her lips, but I could not. My hand shook so much that I was afraid I would embarrass her. I pulled my fingers away and let the back of my hand trace lightly over her hair. It was indulgent, like the touch of warm rainwater.

She caught my hand and pressed her lips to my fingers, and I exhaled in an anxious sigh, my breath quivering as sweet and as skittish as the rise of a dove. When she released my hand, I lingered, grazing the side of her face again, and I felt the damp of a tear. We said nothing more, and we sat for a long while. From that day I noticed a change in her voice when she spoke to me. It was deeper, softer, more affectionate, and sometimes musical. The other students noticed it too and teased me. I did not care.

I did not have any money for a wedding, but a couple in the Nepalgunj church invited us to join their wedding ceremony. We had a double wedding with music and food and much laughter. We even had a little room to stay in there on the church property. It was the happiest day of my life.

Life is such a mysterious thing. I have suffered much, but I have come to a place of contentment. I do not think much about those times when I suffered. If I were not blind, perhaps I would have never heard the message of the gospel. It has changed me. Perhaps I would never have had the opportunity for an education. Perhaps I would never have met Pankali.

We have a little girl now, Rosanie. She leads me about, clutching my index finger in her tiny little hand. She loves to sing to me. Sometimes, after she has had her bath, and she smells of lavender, and her hair is still wet, I hold her in my lap and tell her I love her. And she says, “I love you, too, Daddy.” And I remember all the sadness, and the anger over my disability, and my disappointment, and my suffering, and I think that I have no regrets. I know who I am. I am Dhansing.